Jim Pryor, Harold Witcher, Coy Squyres

Jim Pryor, Harold Witcher, Coy Squyres and Earl Young study maps in Nicaragua

Office Staff - Honduras

Group Photo - Nicaragua

KCB Magazine Wildcatter Article - May 2008

Following is the text of the article that appeared in the May 2008 issue of KCB Magazine. It is reformatted for presentation on this web page. The original article may be viewed in this pdf file.

Black Gold

South of the Border

Story by David Conrads

Photo by Susan McSpadden

JIM PRYOR COUNTS HIMSELF AS ONE OF THE LAST OF A DYING BREED: THE INDEPENDENT OIL WILDCATTER, one of those rare and rugged individuals engaged in speculative drilling in unexplored terrain. Part geologist, part entrepreneur and part cowboy, Pryor (universally known by the nickname "Blacky") shuns established oil fields. He launched his career in the early 1980s wildcatting in eastern Kansas and, over the years, yielded enough success to expand operations to four other states. He operates from the historic Livestock Exchange Building in Kansas City's West Bottoms, though his newest frontier is Central America. In Nicaragua, Pryor and his partners have drilled the first productive oil wells in decades. Pryor believes Nicaragua could be a multi-billion dollar operation when fully developed. And he's looking to replicate that success elsewhere in the region. In fact, he's close to completing a deal with the Honduras government.

"I've always been a wildcatter," Pryor says. "I've never bought a lease that was already producing. Drilling practically in the shadow of somebody else's well where you know you'll hit something that just never appealed to me."

A Kansas City native, Pryor never went to college and never formally studied engineering or petroleum geology. While in his mid-20s (in the late 1970s), Pryor was running a successful construction company when he happened to notice a prospectus from an oil company resting on the front seat of a friend's car. The friend explained that he was thinking about investing in oil wells. Pryor said, "Count me in."

It was love at first sight the day he went to inspect what he had sunk his hard-earned money into. "I just happened to see the sun setting behind the rig, and that's all it took," Pryor recalls. He spent the next five years studying geology and engineering, and he put all of his disposable income into drilling.

By the early 1980s, Pryor had started Pryor Oil Company and established himself as an independent oilman, working heavily in Kansas (particularly the eastern part of the state). He founded Black Star 231 in 1995. To date, Pryor Oil and Black Star have drilled more than 300 wells in four states, about half of them in Kansas.

"From a technical standpoint, I have been successful at being self taught," Pryor says. "My Ph.D. is in experience."

In the early '80s, there were still some old-time wildcatters working in Kansas. Pryor remembers them as mentors. "I probably got three or four hundred years of experience just by following those guys around. I learned most of what I know from old timers." Even today, while making full use of the latest in high-tech equipment, he says some of the old-time techniques are still the best way of doing certain things.

Pryor's single biggest success was a find in Anderson County, located in east-central Kansas. There, on a lease he held from 1990 to 2002, he wound up drilling a total of 57 wells. The wells produced about 100 barrels per day.

When pressure in the Anderson County field began to diminish and oil recovery declined, Pryor decided to get into what's known in the business as secondary recovery. This is a process where an oil field is repressurized by injecting gas, water or some other fluid into the reservoir and forcing the remaining oil toward production wells.

Secondary recovery in the Anderson County field proved to be tricky because fractures in the rock caused the injected water to disperse underground rather than collect in the reservoir and build up pressure. Using existing technology in a new way, Pryor designed and engineered a system to inject cross-linking polymers under pressure, which filled the underground fractures. The result was a recovery of oil that was among the best in eastern Kansas.

THE BLOWOUT

Drilling for oil is extraordinarily expensive and not for the financially faint-of-heart. It costs between $150,000 and $250,000 to drill a well, and most attempts are not successful. Wildcatters can average 24 dry holes for every producing well they strike.

"A lot of people think that oil companies know everything there is to know about finding oil," Pryor says. "They think that technology has gotten so sophisticated we know everything there is to know before we drill. It's simply not true. We have an array of very sophisticated, wonderful tools, but ultimately, we have to drill the well to find out if any oil is down there. Anybody that wildcats drills a lot of dry holes."

Sometimes they drill down and find something very unexpected. That's what happened to Pryor on July 19, 2002. He was drilling in Tennessee on what was the biggest reserve found in that part of the country in decades. The well had a calculated flow of 12,000 barrels a day, or 500 per hour. It was so big, in fact, that the drills hit a pressurized zone at a more shallow depth than expected and the company couldn't contain the pressure. The result, in oil lingo, was a "well-control incident", otherwise known as a blowout.

"When you drill down into the earth, you don't know what's down there," he says. "Sometimes things go wrong and this was one of those times."

With oil gushing out of the hole at a furious rate, Pryor was instantly plunged into his biggest professional challenge, which was compounded when a spark from a bulldozer set the oil on fir'. But that wasn't the worst of it. With the situation mostly under control, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) showed up and took over the catastrophe's management- or mismanagement, in Pryor's opinion.

After butting heads with the EPA and its on-site coordinator, Pryor sued the agency in federal court in Knoxville, Tennessee. The suit consumed all of Pryor's time, energy and financial resources until it was dismissed a year later. Today, Pryor is philosophical about the incident. "Nobody wins a lawsuit against the United States government," he says. "It cost us the wealth we had built up over the years, but we survived and we made our point."

NEW FRONTIER

Although wildcatters are a small fraternity, the high price of oil today and the availability of advanced technology make the climate right for all oil producers. The easy money and the large oil reserves in known areas is long gone, but with crude oil selling for more than $100 a barrel, it is worth going after the smaller pockets that were not as attractive when crude was selling for a fraction of today's price. Additionally, the high-resolution, 3-D seismic imaging equipment, which uses sound waves to map underground structures, was available only to the large oil companies just 10 or 12 years ago. The technology, which has gotten better and cheaper, is now accessible to small, independent oilmen like Pryor.

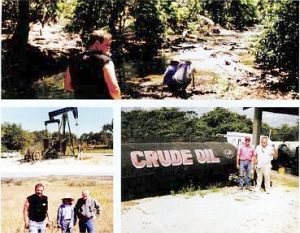

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP:

JIM "BLACKY" PRYOR JUNGLE MAPPING

A SURFACE FAULT IN NICARAGUA.

PRYOR, IN THE WHITE SHIRT, BY A

CRUDE OIL TANK IN BELIZE.

THE FIRST DRILL SITE IN WESTERN NICARAGUA.

PRYOR AT WELL SITE IN SOUTHEAST OKLAHOMA.

His newest frontier is Central America, and the untapped fields that he has been working patiently for more than a decade. Pryor explains, "I wanted to do wildcatting the way they did before the turn of the century. I wanted to live that experience. I wanted to be the first one to go in there and find the very biggest anticlines with the very biggest surface expressions. And I looked around, and those sorts of opportunities were gone, except in isolated areas of the world."

Pryor has made progress in Nicaragua and set his sights on Honduras, where the government in April accepted his proposal for drilling rights. With a compass, a GPS and a local guide, he and his partner, Harold Witcher, first headed into the jungles of Nicaragua and mapped large sections of the country. Pryor believes Nicaragua and Honduras both hold great promise. He and Witcher have convinced financial backers of that promise and formed a company, Industria Oklahoma Nicaragua SA (or Oklanicsa), which was awarded a lease on an 853,000-acre tract by the Nicaraguan government. Pryor hopes to have a final contract in Honduras by summer.

"We've gone into the rankest frontiers, where there is no production for hundreds or thousands of miles in any direction, and have looked for oil in these places," he says. "Now, there is a lot of interest in Central America, but we were way ahead of the curve in 1996."

Pryor notes that wildcatting in Central America presents a very different set of challenges. In Central America, he assumes a much higher degree of risk and also faces legal, logistical and bureaucratic obstacles that don't exist in the U.S. For instance, when he began the effort in Nicaragua in 1996, the new government was just writing a constitution and enacting laws. Pryor and Witcher had to wait until 2002 for Nicaragua to adopt a hydrocarbon law under which foreign operators could legally extract and sell the country's natural resources. They had to wait another two years to complete the first round of bidding for acreage on which to drill.

But the time spent in the country, mapping the jungle, networking with officials and generally building trust and good will throughout Nicaragua paid off Of five foreign bids, theirs was the only one accepted. Pryor struck a deal with Norwood Resources Limited, a Canadian energy company, to drill on the Oklanicsa Concession. So far, two wells have been completed, each on a separate oil field. Pryor expects them to be producing by summer. A third well is being drilled now.

"They appear to be very big, very meaningful oil fields," he says, noting that the geology lends itself to big reserves. "I believe our concession in Nicaragua at some point will make several hundred thousand barrels everyday. I'm sure these oil fields will be producing, to some degree, for the next sixty years."

This year, Pryor has been exploring two oil reserves in Honduras and hopes to strike a deal following a positive environmental impact report. Says Pryor, "You haven't heard the last of this ol' wildcatter."

NOTE: Drilling costs mentioned in the article relate to wells drilled in shallow oil fields, sometimes called "stripper wells". Taking into account wells completed in more productive fields, the cost of wells in the United States runs from a few hundred thousand dollars to tens of millions of dollars per well.